The journey into Paglicci Cave

by Prof. Annamaria Ronchitelli

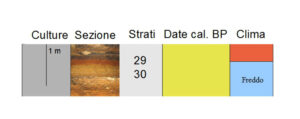

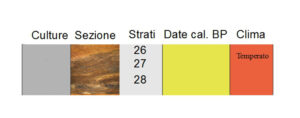

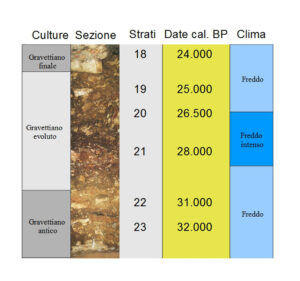

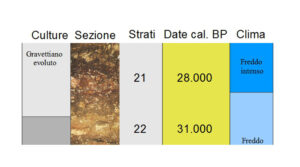

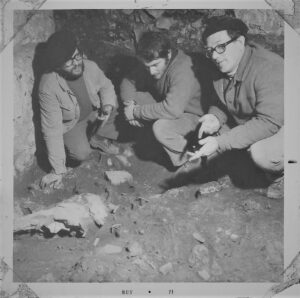

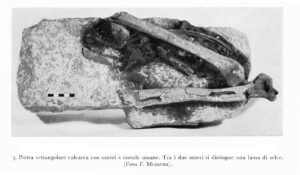

It was way back on 22 September 1971 when, at the end of the annual excavation season, Arturo Palma di Cesnola, Franco Mezzena and Paolo Gambassini discovered, on the roof of layer 22, gravettian (dating back some 30,000 years) in the Paglicci Cave

a human skull pertaining to the burial of a teenage girl. In November of the same year the burial was completely unearthed and recovered

During this work, the hip and humerus of another burial, positioned orthogonally to the first, at roughly the same level, were grazed. But still under about 6m of archaeological deposit.

Almost twenty years were needed to reach this second inhumation, excavating from the layers above, down through the Epigravettian and Gravettian deposits. The skeleton skimmed in 1971, a young woman who also lived in the Gravettian period but lived somewhat later, was finally reached in 1988-89.

Both burials had grave goods, many ornaments, were sprinkled with ochre and constitute one of the finds that have made Paglicci an internationally important Palaeolithic site.

Paglicci Cave

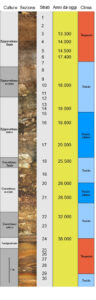

“The Paglicci Cave sequence is formidable – as Palma di Cesnola said in an interview – there are no words to define it. A twelve-metre sequence that contained everything from the Lower Palaeolithic to the end of the Upper Palaeolithic …I spent 30 years excavating this fabulous cave”.

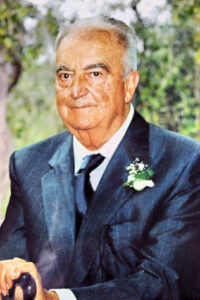

In fact, Arturo Palma di Cesnola conducted his research, in collaboration with Franco Mezzena, in the years 1971-2001, and in 2002 Annamaria Ronchitelli, both from the University of Siena, took over as scientific director, always under the aegis of the local Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio.

Research history and main findings

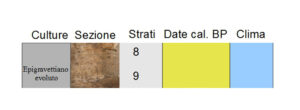

The Paglicci cave discovered by Raffaello Battaglia in 1955, it was initially investigated by Francesco Zorzi on behalf of the Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Verona in 1961-63, in collaboration with Palma di Cesnola and Franco Mezzena then students.

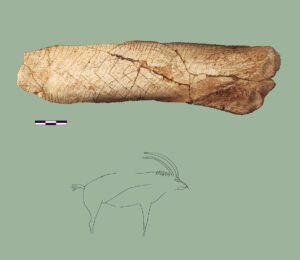

Early years of research interrupted prematurely by Zorzi’s death, but rewarded by important discoveries. These included a partial burial (lower limbs and pelvic fragments), a probably intentional deposit of ‘relics,

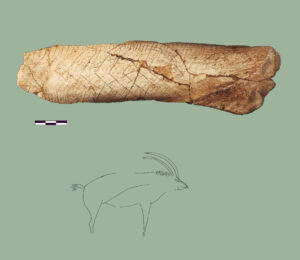

both dating from the Final Epigravettian, around 17,000 years ago, and some artistic engravings on bone or stone with animal subjects, usually aurochs (wild oxen), horses and deer, and birds from the Evolved Epigravettian, around 18,000 years ago.

And, extraordinary in Italy for their uniqueness that persists to this day, the Palaeolithic wall paintings found in the innermost room of the cave, hands and horses possibly the work of the Gravettians.

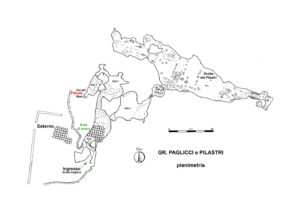

The structure of the cave

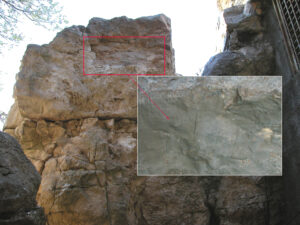

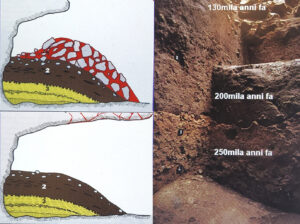

Grotta Paglicci is in fact part of a karstic system that includes: the external area, once called “il Riparo” (the Shelter), actually an ancient hall frequented during the Middle Palaeolithic period whose vault has since collapsed;

the cave of the Pillars; the current entrance hall of the cave, where the main excavation area is located, two other intermediate halls and finally, at the bottom, the hall and apse with the paintings.

Returning to the research

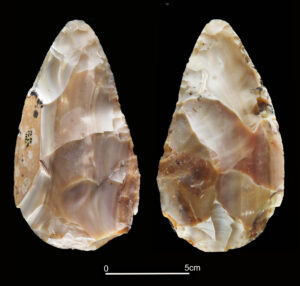

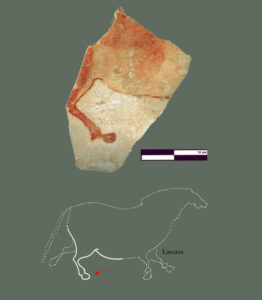

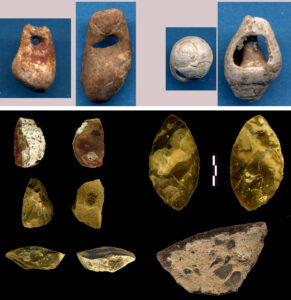

no less exceptional were the findings from the Palma di Cesnola excavations. These include other engraved movable art objects, one of which is from the Gravettian period, dating back some 28,000 years,

the hind leg of a horse painted on a fragment of a limestone slab that has probably collapsed from the vault of the present first room, where it may have formed a frieze (Early Epigravettian, c. 19,000 years ago),

the engraved boulders at the entrance (Evolved Epigravettian, ca 18,000 years ago),

the two burials mentioned above (photo Burial PAII and Burial PAIII). Also hearths, bone plans,

ornamental objects (such as intentionally drilled teeth and shells, lithic industry and abundant meal remains.

All this in 30 years

four weeks in autumn, year after year, down 12 m, taking a few cm of soil at a time, following the succession of stratigraphic levels, over a small area, bucket by bucket,

each to be sieved with 1.5 cm mesh dry and in water; consolidate, survey and photographic documentation;

and then pick out the material washed with tweezers, sorting flints, mammal bones and teeth, micromammal bones and teeth, charcoal, ornaments, all labelled, bagged and sent to the various workshops.

Dozens and dozens of students and enthusiasts have succeeded one another over this long period of time, in exciting but sometimes monotonous and tiring work. To all of them goes our warmest gratitude, knowing full well how low and heavy the ground is, for making the research at this amazing site possible.

WE ENTER…

What is Grotta Paglicci?

is one of the most important Palaeolithic sites in Europe. This archaeological site was identified by Dr. Michele Bramante (owner of the agricultural land where it is located) who was the first to point it out.

Following the interest of various universities and museum organisations, several excavation campaigns were carried out in the 1960s (directed by F. Zorzi, Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Verona), with the support and solidarity of the property owner, and then the extensive research by the University of Siena began. In particular, excavations were directed for many years by Prof. Arturo Palma di Cesnola (1971-2001) and, more recently, by Prof. Annamaria Ronchitelli (2002-2006).

Thousands of artefacts have been found inside the cave. These include lithic industries, faunal remains, human remains and movable art objects (bones and stones decorated with engravings). In addition, there is the only example of Palaeolithic wall paintings known to date in Italy.

Two Palaeolithic burials have also been found, under the direction of Prof. Palma di Cesnola, dating back to around 30,000 years ago (a girl about 12-13 years old and a woman about 25 years old, both with rich grave goods) that are among the oldest in Europe.

The importance of the Paglicci Cave

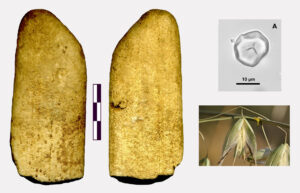

is underlined not only by the artistic finds, but also by the recent studies carried out by the team of Prof. Annamaria Ronchitelli and Prof. Francesco Boschin, who have identified and catalogued the remains of the oldest domestic dog to have lived in Italy (dating back between 14,000 and 20,000 years), as well as a pestle from around 32,000 years ago with starch granules that shed light on the vegetable component of the diet of the time.

Some of the human remains, which have been studied from a genetic point of view, have made important contributions to our knowledge of how ancient European sapiens populations spread.

Historical background

The Paglicci Cave has had a troubled life, due to both geo-environmental events and inconsiderate human intervention. In fact, the karstic composition and geographical position, in full exposure on a valley, and the seismic events that abound in the area, have exposed the cave to erosion and landslide phenomena.

Added to this is the human factor linked to local myths and traditions. In fact, it was believed that a local brigand, a certain Gabriele Galardi nicknamed ‘Jalarde’, had hidden his treasure in this cave. For this reason, some treasure hunters carried out disastrous excavations at the site. They even carried out demolitions with explosives, destroying part of the deposit and encouraging landslides.

The Paglicci cave was only saved thanks to the stubborn and obstinate defence by the owners and the interest of Prof. Raffaello Battaglia of the University of Padua, the palethnologist Francesco Zorzi (director of the Museo Civico di Storia Naturale in Verona) with his collaborator Franco Mezzena, who made the first discoveries and identified the wall paintings, the geologist Angelo Pasa, and Prof. Fiorenzo Mancini of the University of Florence.

It reached its current notoriety thanks to the systematic research of Prof. Arturo Palma di Cesnola of the University of Siena and, more recently, Prof. Annamaria Ronchitelli of the same University.